Introduction: Why a Scrabble School?

Jim Crow laws demanded strict segregation of public facilities.

Jim Crow laws demanded strict segregation of public facilities. Pre-Rosenwald School in Halifax Counties (b), VA. (n.d.) Courtesy of the Jackson Davis Collection, University of Virginia.

Pre-Rosenwald School in Halifax Counties (b), VA. (n.d.) Courtesy of the Jackson Davis Collection, University of Virginia. Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington at the Tuskegee Institute, 1915. Courtesy of the Julius Rosenwald Papers, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago.

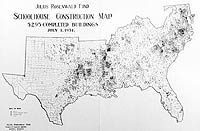

Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington at the Tuskegee Institute, 1915. Courtesy of the Julius Rosenwald Papers, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago. Map of Rosenwald Schools in the United States

Map of Rosenwald Schools in the United StatesJim Crow laws, enacted between 1876 and 1965, institutionalized segregation and racism and denied African Americans rights we now take for granted. Virginia was one of many states that passed these statutes, among them laws that prevented or hindered educating African-American children. Violating these prohibitions could have severe consequences.

Many individuals fought to overcome this injustice. One was Booker T. Washington, a former slave devoted to improving the lives of African Americans through education and founder of the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute. He wanted African-American children to have the same advantage whites were also just beginning to enjoy during the mid to late 19th century—a public education.

In 1912, Washington persuaded Sears Roebuck cofounder Julius Rosenwald to help launch a pilot project to build six elementary schools in Alabama. Inspired by its success, Rosenwald created the Julius Rosenwald Fund, which matched African-American and white donations of money and labor from local communities to build and furnish schoolhouses throughout the South. It was an ambitious goal—practically and politically. From 1917 to 1932, nearly 5,000 communities — including 371 in Virginia — participated in the program. Rosenwald Schools replaced schoolhouses that were often little more than cabins — Rappahannock County had seven in this category — or built a school where before there had been none.

Rappahannock's African-American community seized the opportunity to build modern schools for their children. Scrabble School was the first of four. Its history and the stories of the children who attended the school between 1921 and 1968 are the focus of the Rappahannock African-American Heritage Center.

Timeline

Scrabble School in its historical context.

Video Scrabble

The story behind Scrabble School and what it was like to go to school there.

Audio Recordings

-

Also replaced.